Olympic Flames of ’68

July 19, 2024

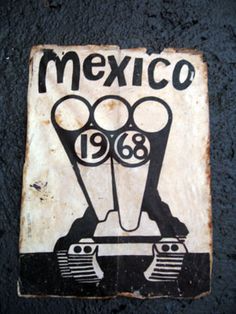

OLYMPIC FLAMES – The Mexico City Olympiad and the Massacre of Tlatelolco

One of the great things about sports is, that much like art, it is perceived as an autonomous social realm, a space for a test of human ability outside of economic or political necessity. Since ancient times, sports offers a space where man’s fate (and more recently, women’s) is not decided by accidents of birth. An athlete does not need to be rich, or well-educated; in this arena, you need only discipline, will-power and training. And of all sports events, the Olympics, with its global span and its UN-backed non-professional ethos, epitomizes the desire for a freedom built around our shared humanity. In the classical period (in the case of the Olympics, a stretch of about a thousand years) the Olympics had a special status, outside of normal bickering between the Greek city states. This was marked by the “Olympic Truce” where ongoing disputes and even warfare were brought to a halt, marked by the famous Olympic Flame.

2024 is an Olympiad year, and with Paris, the most civilized of cities, hosting, spirits are high. It is in this vein that the Metrograph offers us a screening series, “Art Cinema, Olympiad, and the World” which promises both films that offer in some cases “high-style depictions,” and in others “kaleidoscopic investigations of the diverse set of social, economic, political and industrial networks that operate around each of the games.”

They have several documentaries, including significant contributions such as Masahiro Shinoda’s Sapporo Winter Olympics, and Carlos Saura’s Marathon. Also included is The Olympics in Mexico by Alberto Isaac (1969, 111 min.).

The Olympics in Mexico (Dir. Alberto Isaac, 1969)

A bit of background. The 1968 Olympics were held from October 12 to 27 in Mexico City. They were the first ever in Latin America, and the first in a Spanish speaking country. The government of President Gustavo Diaz Ordaz spent some $150 million dollars to showcase Mexico as a worthy host. The architectural evidence can be seen across the city to this day, but the games themselves live in the shadows cast by the massacre that took place at the opposite end of the vast city from the stadium some ten days earlier.

Mexico was hardly the only country where ’68 was a time of youth rebellion. But the form that unrest took in a country that has been a republic since the early 19th century, but was in 1968 a one-party state run by the PRI, the Party of the Institutional Revolution — ultimately one of the longest lived regimes in 20th century history — differs significantly from stories emerging from Paris or Berkeley the same year, resembling more the Soviet treatment of the youth of Prague.

Tanks confront students in Tlatelolco Plaza, October 2, 1968 / El Grito. ( Dir. Leobardo López Arretche México, 1968)

The story starts on the campus of UNAM, the Mexico National Autonomous University, the star academic institution of Mexico. In June, 1968 the overreaction of the school authorities to a fight on campus led to a series of strikes and demands for student control, guaranteed rights of assembly, release of political prisoners. A strike committee was formed. The struggle struck a chord, and on August 27th a call for a demonstration in the Zocalo, Mexico City’s main square, and the site of the Presidential Palace was answered by over half a million people, far and away the largest demonstration in the country’s history.

The take over of the Zocalo was the last straw for the government. With the Olympics drawing near, the government organized a response to end the student movement — Operation Galeana, a joint effort including the Army, elements of the Presidential Guard, riot police, as well as plain-clothes provocateurs. A demonstration called for October 2 in the Plaza de Tres Culturas, a modern development named for the presence of pre-columbian and colonial era ruins, was their target. Thousands of students gathered in support of the strike committee. A helicopter flew low overhead. A series of signal flares were ignited, shots were fired, and the killing began. There were some five thousand troops with some two hundred armored cars surrounding the students and preventing escape. There was surveillance and crowd control equipment provided by the US. The killing went on all night. The roundup for days. The number of dead is unknown, but estimates run to three or four hundred, with about a thousand wounded and thousands more detained.

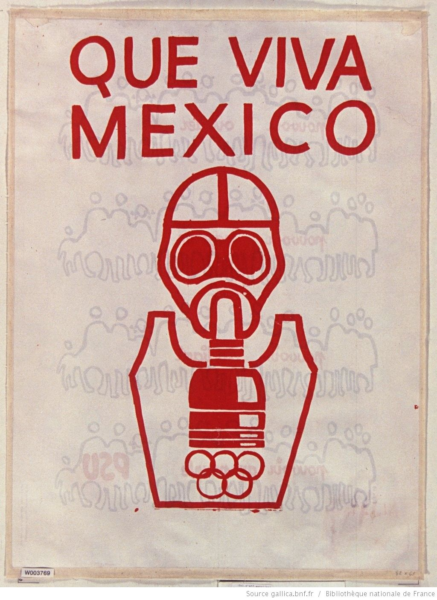

I was a young student from Berkeley when I went to Mexico City for the first time in the winter of 1968. Although both the Olympics and the student demonstrations were over, the aftermath was unavoidable. The family I was staying with talked about the stench of the bodies burned at the army base in Chapultepec Park wafting over their upper middle class Polanco neighborhood. And a quiet war of grafitti stencils and posters was still visible as well, posters that made clear the deep connection between the massacre and the Olympics.

All this is just to say that to mention the 1968 Mexico City Olympics is to talk about the massacre by the Mexican government of hundreds of students, many of them from the same campus, the Ciudad Universitaria, that was the site of the Olympic stadium.

So what about the movie? At this point I have to seriously question the programming talents of the Metrograph team. This is a film that should not be shown without significant context.

Admittedly, the film itself was a tour de force. 750,000 feet of film shot in a wide screen format with some 400 on crew. The director, Alberto Isaac had himself been an Olympic competitor in his youth. The film was a significant propaganda victory for the Mexican government and the PRI. It was even nominated for an Oscar when it came out in 1969.

The Olympics in Mexico (Alberto Isaac, 1969, 240 min.)

The programmers at Metrograph include an essay from a well known British author on sports, Geoff Dyer. https://metrograph.com/the-olympics-in-mexico/

Unfortunately, the review seems to emerge from a parallel universe where the Olympics are not just autonomous, but entirely separate from Earthly events. It feels a bit like reading a review of Leni Reifenstahl’s Olympia (1938) in a Nazi newspaper.

To be fair, Dyer certainly noted internal contradictions in his essay. After dwelling on the beauty of the special effects (lots of slo-mo here, at a time when it still required special cameras) he notes that the film has an all-encompassing idea of harmony to the point of soft-pedaling the few signs of politics creeping into the event itself. A key moment in 1968 was the Black Power salutes of two American athletes, Tommy Smith and John Carlos, who raised their fists during the the playing of the US national anthem, accompanied by Australian athlete Peter Norman. The demonstration has been called one of the most overtly political statements in the history of the modern Olympics. As Dyer notes, the film shows the moment, but without context, essentially burying it.

“Where’s the harm in that?” one may ask. There is none, if you assume that the Coca-Cola ideal of teaching the world to sing in perfect harmony—rather than freedom from the realm of necessity or whatever—represents the endpoint of political struggle and le cinéma engagé. Geoff Dyer “The Olympics in Mexico”

On the other hand, even the Wikipedia article about the 1968 Olympics has several paragraphs detailing the links between the Olympic events and the massacre, as a bit of homework might have revealed. The Mexican government continued to perpetrate the coverup the documentary The Olympics in Mexico is part of for over thirty years.

Although the documentary ends with a spokesman calling on the youth of the world to gather again in four years, the shadow of the student deaths continued to hang over the PRI throughout the following decades. But it was not until Vicente Fox, the first president from another political party in 70 years, opened an investigation in 2001 that the facts of the massacre started to emerge. US documents showed that the then Minister of the Interior,(and later President) Luis Echeverria Alvarez who was responsible for the deaths was a CIA asset. Attempts were made to charge him with genocide.

As someone who teaches research both for documentary filmmaking, and for documentary film studies, I routinely urge my students to do two kinds of historical investigation, diachronic and synchronic. Diachronic suggests across time, in this case, one might develop a historical sense of Olympic documentaries from the earliest deployment through more recent efforts. The Metrograph programs seem to have done something along these lines. But just as important is synchronic research. What was happening in the rest of the society at the time of the film you’re looking at? Here, the failure of the programmers seems monumental. The unfortunate result is to perpetrate a coverup which was only ever a fig leaf for slaughter.

The Metrograph’s Olympic series tries to offer some kind of social context, although I thought it odd to enlist Kidlat Tahimik’s Turumba for this effort. They might have done better to screen El Grito, a collectively produced documentary from the period that details the student movements struggles, and ends with lighting of the Olympic flame. Lovingly restored by UNAM, it is worth watching if you speak Spanish. Oddly, its narration was written by Oriana Fallaci, who was one of the many observers wounded by gunfire at the plaza.

As a final note, I asked the Mexican filmmaker, Luis Lupone, if he knew anything about The Olympics in Mexico. This is his reply:

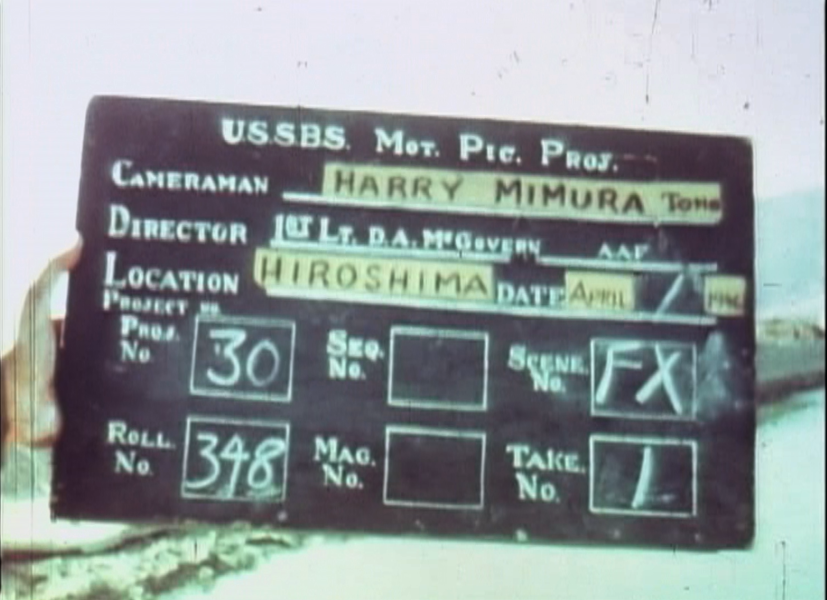

The documentary was made by the best cameramen and film directors at the time. Just as it was the first Olympics to be broadcast in color in history, the government wanted a film worthy of showing the greatness of the event, which is why it took a year to edit and only premiered in October, 1969. Evidently, as you say, it is a propaganda film about the achievements of the repressive state. The paradox was that the equipment purchased by the government in July 1968, Arri 16 and 35 mm cameras. 200 and 400mm telephotos, O’Connor hydraulic tripods, Sennheiser directional microphones, this whole set of equipment debuted in the massacre of October 2, where from the 14th floor of the Foreign Relations Tower on one side of the Plaza de las Tres Culturas they filmed more than 80 hours, from October 1 to October 3 October. No one has seen that material; rumors say that it was burned as well as many student corpses. Others say that Luis Echeverria, who was Secretary of the Interior at the time, and was the one who orchestrated the massacre, has it in his house.

Martin Lucas – July 18, 2024

| More: Uncategorized

Slovenia On My Mind

June 22, 2018

Slovenia On My Mind

To anyone born during the Cold War, the crossing seemed like a secret door between worlds. The train stops at the border. The passengers must step off. The sleepy station features low yellow stucco buildings with red tile roofs – something I learn later is a legacy of the Austro-Hungarian empire. As soon as I cross from the Austrian station through customs to the Slovenian one, the kaleidoscope shifts, the geometric patterns lose a bit of their parallel nature and we’re in a non-euclidean universe. The window boxes bursting with red geraniums take on a libidinous note after the gray byways of Austria. A kind of frowsy time machine sets me in a first class coach from another era. The upholstery on the Slovenian train is in faded grays and violet, the seating is velvet, and there are tiny sconces between the heavily curtained windows featuring cut class vases, long empty of flowers. I feel like I’ve stepped on the set of Hitchcock’sThe Lady Vanishes.

The railway architecture gives way to the distinctly Balkan homes of poured concrete, large and blocky with bits of rebar sticking up where another floor may go. And then through Maribor, to Ljubljana. It was 1993. I was met at the station by a young woman who was the director of Radio Študent, one of the sponsors of my visit, built around a screening of tapes from Paper Tiger Television, the video group I was part of at the time.

Ljubljana Station

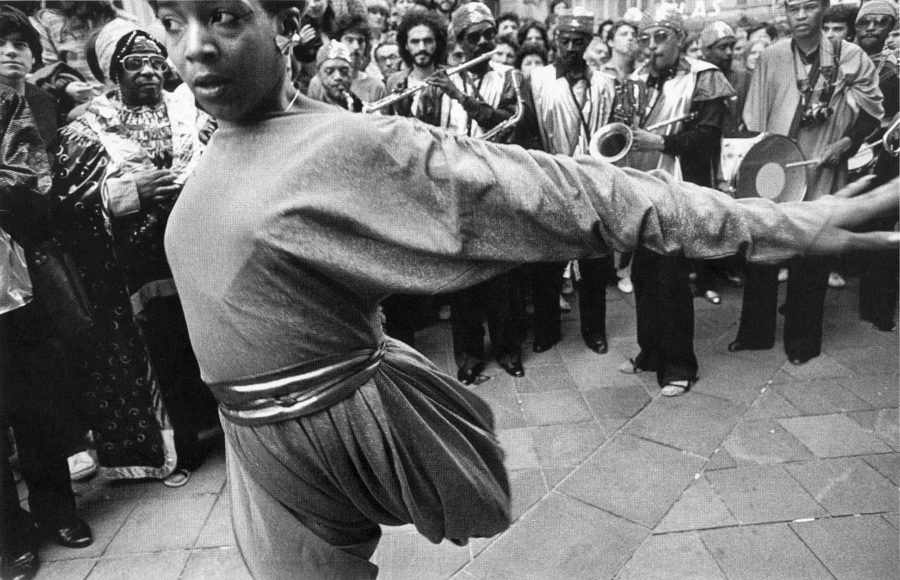

Although Slovenia has a long history as part of various empires, from the Roman to the Austro-Hungarian it is now a small nation of some two million, one that has often been on the border between peoples and empires. Ljubljana is not a large city, and my first tour did not take long. The Three Bridges. A lovely town square. The Museum of Art. And we wound up in a beer hall with a medieval cast. Thick walls, benches, a stone floor. And by himself at one of the tables, a guy in a tee shirt and jeans. I am introduced to Slovenia’s leading philosopher, Slavoj Žižek. We talked about the usual stuff, art, politics, the activist media I had come to screen. Then to Radio Študent’s studios, where I heard the history of this station which had started as part of the anti-Fascist underground resistance in WW2. The last stop on my tour of Ljubljana was a building that had a former life as a Benedictine Monastery. It was from here, I was told, that “Space is the Place” afro-futurist musician Sun Ra and his Arkestra had set out in an unauthorized jazz procession that spelled the beginning of the end for Tito’s rule in Slovenia.

Sun Ra and Arkestra, Ljubljana 1982. Courtesy of Radio Študent

The screening was a big success. I remember being teased about the Marxist analysis of the American media offered in our tapes. What could America offer to socialist thought?

For me this Slovenia was a kind of funky paradise — a conceptual art piece, Neue Slovenische style, with music by Laibach, the mock-fascist industrial group, and acerbic asides from the art collective IRWIN. A country full of young artists and intellectuals who kept themselves free from the crushing weight of ideologies of East and West. It was a space that was important in my own mind during the rise of what is now called neo-liberalism, the idea of a small culture making art and politics in an independent and fair-minded vein with a strong dose of humor.

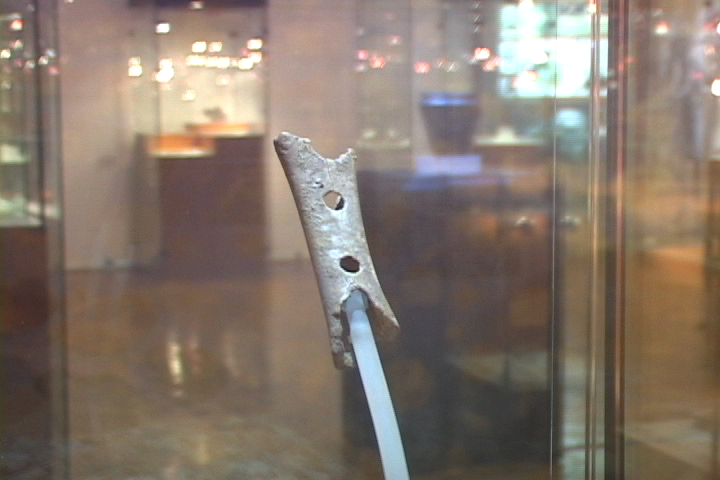

It was years before I went back, this time to a country suffering seriously from the 2008 crash, and on a train from Zagreb where I had a chance to meet artists from across the Balkans with the WHW curatorial collective at Galerija Nova. Now I had come to film the famous Neanderthal flute, famous in Ljubliana at least, at the Museum of Natural History. The museum itself was still a monument to 19c science, a brass plaque with Emperor Franz Josef’s profile in the lobby. Tall windows and dark corridors full of vitrines and obscure specimens collected in the abundant geography of this nation small, but redolent of history.

Divje Baba Flute

The last Ice Age had covered Europe with glaciers that ended exactly in these alps, making Slovenia and Croatia’s mountain caves the home to the Neanderthal. Here the flute suggested that this maligned hominid made music and buried their dead with ceremony, belying the myth of their caveman rep. The museum’s lead scientist explained the importance of the discovery in terms of the new light it shed on the Neanderthal, and how the discovery in a cave in the Slovenian Alps was totally dismissed by American scholars.

A third visit during a summer vacation in 2014, the crash long over, The stay was pricey, the restaurants charming, the tourists clogging the riverfront and lining up for a tram to the mountaintop castle. Globalization had set in. Slovenia had rebranded itself as a cute tourist site living on Airbnb and Trip Advisor, the price of deterritorialization and proximity to the Dalmatian Coast.

There is one other image of Slovenia, not from my own experience, but from the film work of Želimir Žilnik, a Brechtian moment in one of his films, Fortress Europe, a lightly done fiction about a Russian family trying to get to Italy. Two border guards, a man and a woman, show how to sneak across into the EU. It is perhaps these last two images that are the most useful for forming a picture of Slovenia today.

“Fortress Europe” (Zelimir Zilnik, 2000)

http://www.zilnikzelimir.net/fortress-europe

As part of Tito’s Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, Slovenia had been a star, the lead example of the “Self-managed socialism” that was the invention of native son Edvard Kardelj. Slovenia was the first formerly communist country to join the Eurozone after the breakup. The breakup of Yugoslavia was accompanied with a rhetoric where nationalism turned to ferocious racism and famously occasioned vast atrocity. Slovenia adroitly avoided most of the terrifying fallout since it declared independence in 1990. But life as a small independent country has not been easy, and it would be impossible for an outsider to catalog the complex ups and downs of democracy here.

In June, Slovenia had elections. The top vote getter supported by Hungary’s Orban, has the populist anti-immigrant stance of governments popping up across Europe. It was that election that prompted me to think of the image of Slovenia that I somehow wanted to keep in my mind.

When I first went to Slovenia, I stayed in an apartment in a public housing block. The park nearby featured a statue of Edvard Kardelj, Tito’s right hand man, and the inventor of Self-managed socialism. Accused by Stalin of being on the border of Trotskyism or council-communism, this much lauded but hard to characterize system seemed mainly to serve to keep Yugoslavia out of the control of the Soviet economic zone, allowing for loans from the West and Yugoslavian guest workers in Western Europe. Maybe it was just the political expression of a kind of impossible independence. Although it is worth remembering that the Yugoslavian resistance to the Nazis was very real, and very different from the response of many European nations to the occupation.

From being at the forefront of workers self managed socialism to a poster child for European social democratic capitalism, to drifting slowly toward authoritarianism what happened? The signs were there. [footnote: An intriguing history of the magazine Praxis, a home for the post-Stalinist left that fell apart when the collapse of former Yugoslavia lead to the rise of Serbian and Croatian nationalism was recently reprinted by The Jacobin.] The “Non-aligned Movement” (Nassar, Tito, Nehru and Nkrumah) allowed Yugoslavia wiggle room as part of what was in many ways a third world movement. Was that image of a third way always a bit of an illusion? No doubt. But just as an escape from binaries, it felt important.

The recent elections gave former Prime Minister Janez Jansa and his right-wing Slovenian Democratic Party the largest number of seats. Parliament meets today, on June 22nd. And the other parties have vowed not to form a coalition with Janša. Janša is a fan of Hungary’s Orban, and it was noted that one Hungarian media mogul linked to Orban took control of a couple of media outlets in Slovenia. The authoritarianism and anti-immigrant populism that has spread across the globe is getting its day in Slovenia.

Slovenian Democratic Party Poster, 2018.

See:http://www.pengovsky.com/2018/05/30/2018-parliamentary-election-bells-and-dog-whistles/

Is this was still the same country where a jazz procession from a former Benedictine monastery could start a revolution? The original procession was in 1982. One can only hope Sun Ra would be allowed in today.

Marty Lucas

Footnote: Radio Študent, Ljubljana is still alive and well: https://radiostudent.si

And you can view a 32nd Sun Ra Anniversary Memorial Procession in 2014:

| More: Uncategorized

BUTTON, BUTTON…

January 04, 2018

As if to assure the world that his first year of collusion, coverup, racist utterings and sabre rattling were not an aberration Donald Trump’s latest tweet is an explicit embrace of nuclear war and its destructive potential.

Puerile size comparison aside, nuclear war is not a pissing contest. While the deaths in Nagasaki and Hiroshima are only an arguable one percent of the total casualty figures for WW2, they represent a vast increase in the acceleration of the pace of death, as in each case tens of thousands died in moments. Today’s weapons are much more powerful than those of 1945. A variety of studies offer potential death counts, but Trump clearly relishes the notion of threatening the millions of deaths and vast destruction which should result from even a limited nuclear engagement, if such a thing is possible to limit.

As disturbing as the tweet itself is a look suggests that close to half a million Americans are excited with this kind of posturing. The implicit deal is a terrifying one. Much like the citizens of North Korea, Americans are offered gratification based on their leader’s potential for instant mass murder. Clearly, many find this comforting. Kim Jung Un can at least claim with some veracity that nuclear weapons are essential for maintaining his rule. In a country like ours, which has an arsenal big enough to destroy every major city in the world, it is evil.

Nike Missile Warhead / Cold War in 24 Frames / Martin Lucas

You don’t have to be a deep reader of The Lord of the Rings to understand the corrupting effect of being the one in sole charge of total destructive power. Elaine Scarry’s book Thermonuclear Monarchy lays out some of the distorting consequences for democracy. Recent calls to create some kind of alternative to the single hand on the button such as the initiative of the Union of Concerned Scientists are indicative.

I grew up in the household of a nuclear engineer during the Cold War, aware even as a child of the functionality and destructive potential of nuclear weapons, a potential that was reinforced by the ‘duck-and-cover’ nuclear air raid drills that were a regular feature of my elementary school education. In the 1950s and 1960s, the possibility of nuclear war was a global nightmare. As Bob Dylan said in Talking World War Three Blues, “everybody’s having them dreams.” That nightmare was only ever dormant, but it has been resurrected.

Union of Concerned Scientists:

(https://www.ucsusa.org/nuclear-weapons/us-nuclear-weapons-policy/sole-authority#.Wk5nira-LMU)

Scientific American:

| More: Uncategorized

Codes + Modes Symposium Coming Up!

March 07, 2017

The Hunter Integrated Media Arts MFA Program is sponsoring Codes + Modes: Reframing Reality, Virtuality and Non-fiction Media. I’ve been working hard with colleagues Andrew Demirjian and Heidi Boisvert (NYC College of Technology) on what should be an exciting event. Join us for a stellar line up of curated talks, panels & a performance & art exhibition that aim to create an intervention into the often uncritical excitement about virtual reality, augmented reality, artificial intelligence and machine learning to establish a space for conversations about long-term socio-cultural and neurobiological impacts. Presenters will discuss how theorists, activists and artists can develop useful frameworks to explore the complex implications of using emerging technologies. Featured speakers include Lev Manovich(Director of the Cultural Analytics Lab, CUNY Grad Center), Mandy Rose (Co-Director of i-Docs), Daanish Masood (Co-Founder BeAnotherLab), and Lina Srivastava (Founder of Creative Impact & Experience Lab), Dan Archer(Founder of Empathetic Media) and Geetu Ambwani (Principal Data Scientist at Huffington Post).

Register here: http://www.hunterintegratedmedia.org/reframe/

Please share: https://www.facebook.com/events/390015031374841/

| More: Uncategorized

Hiroshima Bound @ Filmette Film Festival

November 12, 2016

I’m pleased to announce that Hiroshima Bound will be screening at the inaugural Filmette Film Festival at Harvestworks on Sunday, November 20th at 4PM. I hope you can join us for this screening, one which looks to be a fairly rare opportunity to see the film here in New York.

Hiroshima Bound will be screening at the inaugural Filmette Film Festival at Harvestworks on Sunday, November 20th at 4PM. I hope you can join us for this screening, one which looks to be a fairly rare opportunity to see the film here in New York.

The link is:http://www.filmettefestival.com/schedule/

WHEN: Sunday, November 20th at 4PM

WHERE Harvestworks

596 Broadway #602 New York NY 10012 (Between Houston and Prince)

| More: Uncategorized

Hiroshima Bound at Roosevelt House

September 15, 2016

I am pleased to announce that my film Hiroshima Bound will be screening at Hunter College’s Roosevelt House Public Policy Institute under the auspices of the Hunter Human Rights Program. The screening will be followed by a discussion with Professor Yukiko Koga from the Hunter College Department of Anthropology.

This is an RSVP event. If you are in New York, please come!

Date: Friday, September 30th.

Time: 6PM

Place Roosevelt House 47-49 East 65th Street

between Park Av.and Madison Av.

For more info + RSVP : http://www.roosevelthouse.hunter.cuny.edu/events/hiroshima-bound/

| More: Uncategorized

Following the North Star: Kim Jong Un and modernist missile aesthetics

June 20, 2016

North Korean “Pole Star” submarine-launched ballistic missile, April, 2016.

ROCKET DEJA VU

The latest missile launching from North Korea, which took place in April, was announced actually, belatedly, to distract from the flopped launch of another missile. The missile shown in the video provided by the North Korean government was fired from a submarine. The audience was small, comprised mainly of Kim Jong Un himself. The launch takes place in an oddly intimate cove, a site more suited for a beach barbecue.

I couldn’t help but be struck by the accompanying image, which showed a familiar black and white paint job on the missile, and the curious name of the missile, dubbed “Polar Star.”

We expect history to repeat itself. It doesn’t, really, but certain tropes, not to say memes, do reemerge. If they seem farcical, they’re no less dangerous for that.

As a child during the Cold War, with a parent involved in nuclear weapons development, I remember going to the award ceremony. Sitting on bleachers in the hot California sun, watching a group of Navy bigwigs sweating in their uniforms, looking tiny next to the mockup of the then new (I’m guessing 1962) Polaris medium-range ballistic missile. It stood, cool and abstract in a coat of flat white with linear black, in strict horizontals like a composition by Malevich or Mondrian. I was young enough and short enough to crawl under the missile’s rocket engine nozzles and look up at the snazzy black on white paint cylinder, topped by a nose cone that promised 600 kilotons of nuclear explosion. (“Fifty times more powerful than the Hiroshima bomb, in the parlance of the times.)

Polaris nuclear missile launch, circa 1960. (Note black on white paint job).

At that time, America’s first submarine-launched missile was dubbed the Polaris. The ability to launch some dozens of these missiles from untraceable locations under the surface of the seas made this a key component of the ‘triad’ the three parts of America’s ability to offer “mutually assured destruction” (this missile was designed to hit the enemy after they had launched a strike at US targets.) The other two being ground-launched ICBMs, and long-range bombers. There were some 41 of these submarines, each armed with 16 missiles.

In terms of the name, it is important to remember that Polaris was a US Navy development. The naming convention for land-based missiles tend to draw heavily on ancient mythology, favoring Greek, e.g. Titan, Ajax, Atlas, Hercules, or the odd Norse god, e.g. Thor, the first ICBM. While the trope of naming missiles after Greek demi-gods is obvious, with the typical attribution of divine powers to atomic weapons, the use of a star’s name is less so. In fact, the word “Polaris” to indicate the North Star sounds classical, but was actually coined in the late 1700s. And Pole Star, the name used for the North Korean missile, is a variation of the name. Perhaps the name refers to the guidance system, a key feature when the weapon was new.

And the Polaris, developed principally by Lockheed, represented something new. First off, it was a Navy operation built over objections from Army and Air Force. Creating a complex weapon system from scratch, one that could launch a small medium-range ballistic missile from any where a ship can go, and deliver an atomic warhead to a target some thousand miles away with with accuracy presented a challenging set of technological problems in propulsion, guidance, warhead miniaturization and overall size. With the impetus of the Soviet Sputnik the Navy approached the problem not just with new technology, but with a new design approach, PERT, or Program Evaluation Review Technique, which allowed for iterative interlocking design efforts and became a standard for certain types of large corporate design efforts.

But the Polaris, as innovative as it was, was first launched in 1960. Newly elected President John F. Kennedy, himself a Navy man, watched a launch. The new President, and the new trim and deadly missile were a timely match. Polaris-armed subs were in service during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. The Polaris went out of use in the US Navy around 1980, replaced by the Trident.

President John F. Kennedy watching launch of Polaris missile at Cape Canaveral, Nov, 1963.(JFK Presidential Library)

So why would North Korea develop a missile that is both named identically with an obsolete American one that went out of use thirty years ago, and uses elements from the same design palette? The choice of name seems like a clear reference to the US missile. Other North Korean missile names seem to be more geographical. For example, Taepodong, the name of the North Korean ICBM missile series, means “Large Watery Place” and seems to reference the North Korean launch site. (This is not to make fun. The Magna Carta was signed at Runnymeade, which could be interpreted similarly.i)The North Korean submarine launch platform itself is an old Soviet model. And Soviet missiles tended to be painted army green, and had names like R-11 and R-13. Maybe just not exciting enough for someone who obviously loves his weapons of mass destruction.

BALLISTIC STYLE TOUR

I want to take a style tour of submarine-launched missiles. But first, I have titled this essay “missile aesthetics.” Can one speak of the category of the aesthetic in relation to weapons systems? This essay begins by looking at design elements of the submarine-launched ballistic missile. And when I say design, I refer initially to what is often thought of as product design. Not all products are designed this way. The most familiar, at least for myself, is probably automobile design. This is a field where a design process starts with a sculptural model that more or less disregards engineering, and then the engineers attempts to fit the actual vehicle into that skin. “Automotive design is the profession involved in the development of the appearance, and to some extent the ergonomics, of motor vehicles or more specifically road vehicles.” as Wikipedia would have it. So initially I am looking at the exterior appearance, and the trim. But ultimately I want to use the category of the aesthetic to examine the submarine-launched ballistic missile as a “cultural object,” a set of technologies that are designed to relate to other aspects of culture.

Indian Sagarika missile launch, 2013.

While the US Press tends to focus on bad boy Kim, and his retro rockets, he is one of the small players in the “Nuclear Club.” Around the world there are moves to develop a new generation of nuclear weapons. The meetings between President Obama and India’s Prime Minister Modi in early June, billed as cordial and resulting in an agreement for India to purchase half a dozen US nuclear power plants, not to mention a major defense agreement, suggest that there is at least tacit approval for the Indian development of a hugely extended nuclear weapon capability in the form of a nuclear armed submarine production program. (right now, their the only ones other than the security council five who have a ballistic missile sub.)

It is worth noting that the Indian missile, the Sagarika, ( सागरिका,Sanskrit for “Oceanic”) launched for the first time from an India-built submarine in 2013, also seems to sport the classic black trim-on-white color scheme.

The Chinese have on offer the JL-2 (巨浪-2) or “Giant Wave” Their missile offers a different design profile. The photos suggest something more like a giant airborne grain silo with perky blue trim.

Chinese JL-2 Giant Wave missile launch

And while the US is quietly applauding India, presumably as a potential deterrent to Chinese ambitions, the Chinese themselves have a recent deal with Pakistan to build eight subs. While these are not explicitly for nuclear weapons, the defense press has suggested that, given Pakistan’s agile missile-production industry, the purchase opens the possibility.

The French contender, the M51, looks frankly penile, if the penis was re-envisioned with turquoise and white stripes on a black background, perhaps by Nike.

French Navy M51 missile on launch.

HOW TO TALK ABOUT DESIGN?

In his seminal essay on post-war Italian scooter design, Dick Hebidgeii notes the difficulty of locating any discussion of modern industrial design. These are processes that are extended through time and space, and situated in several sites of production and consumption, from design, and manufacture, through advertising, consumer judgement and varied consumer use, all changing (in relation to each other) over time. His answer, at least in that essay is to create what he calls a ‘dossier’ based on original documents.

By their nature, nuclear weapons, which are designed for mass destruction, rather than mass consumption, would seem to fit a consumer design model poorly. But in a way we are all consumers, at least in those countries where our tax dollars pay, and pay very handsomely, for nuclear weapons. And, as secret weapons, the documentation of design and purchasing decisions is mediocre.

But these weapons are commodities. Here is a description of the SPO, the Navy’s Polaris design group:

“An alchemous combination of whirling computers, brightly colored charts, and fast-talking public relations officers gave the Special Projects Office a truly effective management system. It mattered not whether parts of the system functioned or even existed. It mattered only that certain people, for a certain period of time, believed that they did.”

Harvey Sapolsky “Polaris System Development, (quoted in Spinardi.)

In his book From Polaris to Trident: The Development of US Fleet ballistic missiles, Graham Spinardi notes that there are at least two major theories about how weapons development happens. One assumes a rational actor who assesses needs and develops weapons accordingly. The other assumes that in a democratic society at least, the choices are political, and fall into the same tactical areas of salesmanship that all politicking implies.

This brings us back to a place where a design-based discussion has relevance, because we are talking about the creation or manipulation of human desire. Not desire for goods in the normal sense, as it is the rare individual that gets their own missile, but the more amorphous desire to be part of the weapon-owning nation.

So what are we getting when “we” buy a nuclear weapons system? A sense of security? Satisfaction that we are citizens of a great nation? In a post-Cold War world the classic notion of “deterrence,” AKA “mutually assured destruction,” seems weaker than it did in the Cold War era. (In fact, deterrence probably is a big factor for Kim, who can look at the fates of Saddam Hussain and Muamar Khaddafi as a good reason to have weapons that would preclude easy “regime change.”)

To get at the role of nuclear weapons in terms of nation building and its corollary, “citizen formation,” India is perhaps more instructive than North Korea. While the Indian nuclear program goes back to the founding of the Indian state in the late 1940s, the modern version is explicitly linked to right wing Hindu-based politics, in the form of the BJP which took office under the leadership of A.B. Vajpayee in 1998 and conducted nuclear tests a few months later. Recommended viewing is Anand Patwardan’s stunning epic doc “War and Peace” which offers a complex and unsettling depiction of the origins and development of the Indian nuclear program in a mix of mythology, Hindu nationalism, and macho weapon-love. I mention India and Patwardan’s film not to specifically indict India. What is important is to ask how nuclear weapons “work,” how they mean in the contemporary world, a world of globalization, neo-liberalism and a general global trend toward national chauvinism and strong-man governments.

The useful question is probably not why does Kim Jong Un’s Korea develop a weapon that looks to be an imitation of a Cold War stalwart, but in what ways are things different now? How has the meaning of these weapons changed? With the Cold War long over, and socialism discredited as an economic alternative, we are in a kind of late late capitalist period. I can’t hope to answer these questions here, but I would like to speculate on possibilities.

DESIGN POLITICS

Weapons systems are a commodity, and they are packaged to impress. Hebidge notes that the Vespa, ironically the work of a WW2 bomber manufacturer, was designed for a new type of consumer. Rather than a motor cycle, the very name of which emphasizes its mechanicality and power, the scooter hides its engine, sheathing its works under smooth curves. The scooter comes out of the early Post-War era, but defined itself in the 60s. The Polaris is from the Era of Cool, the late 50s and early 60s, a period of skinny ties, bebob jazz, and cigarettes that put death “a neat, clean quarter inch a way. What is different about this missile in 2016, as opposed to 1962? How does it mean? What is its “cultural significance” in a globalized world?

Lambretta ad, circa 1967

THE MISSILE-AS-PENIS THING

One of the standard tropes about missile-production is the missile-as-penis. The classic cartoon shows a lab with the caption “Scientists comparing missile size.” A missile is a projection of power. The gendering of weapons, and of anti-nuclear movements is subject for another day. But there is one aspect of the penis that might help us understand the role of the nuclear missile as culture actor.

In her analysis of The Story of O, psychoanalyst Jessica Benjamin notes the role of the penis of the sadist. It represents the sadist’s desire, but indirectly:

“The penis represents their desire, and through this indirect representation they will maintain their sovereignty. By interposing it between her and them they establish a subjectivity that is distanced, independent of her recognition. Indeed, they claim that their abuse of her is more for her “enlightenment’ than their pleasure. … Their acts are carefully controlled: each act has a goal that expresses their rational intentions.”iii

Is this a useful way to understand a missile? Here, the severe black on white look, and the lack of aerodynamics can help serve create the veneer of rationality for nuclear weapons, particularly weapons whose sole purpose is to destroy entire cities. “This missile is a war-preventer.” says that sober exterior. The comparison may be farfetched, but a couple of things make me feel it is a useful one. I am not suggesting that the relationship of the citizen to the State is necessarily sado-masochistic. But the power equation with nuclear weapons is also skewed. I realized when I was twelve that the threat of a Soviet invasion was less frightening to me than the existence of weapons that can destroy life on Earth. So the element of fear, total fear, is brought into the Social Contract. The other thing is that nuclear weapons are the one kind of weapon designed not to be used. Their value is exactly in the fact that they are frightening, it is a power that works affectively and emotionally. Here again, the sober stylistics help emphasize the element of rational control.

Nation states are imagined communities. The role of nuclear weapons in creating those imaginaries is something complex. We are asked in a certain way to identify with the power. This power is in one way the state’s monopoly on violence. Aside from the problem I mentioned before, that the potential violence that is supposed to make us feel secure under the aegis of the State tends to do the opposite, there is another problem. Weapons systems, the military units that deploy them and the industries that spawn them tend toward an unsettling autonomy. The weapon-system gone rogue is a classic thriller plot. In this case, think Red October. Suffice to say always something problematic about weapons from the point of view of the State. In 1000 Plateaus, Deleuze and Guattari create the term “The Nomadic War Machine,” and note that it is “exterior to the State.”

In North Korea, weapons development is part of a larger picture where one leader rules the State, and the Party, and heads the military as well, and leads all three, not to mention the People, in an ongoing struggle against the capitalist world. In this equation, citizens are invited to see the power of Kim and the power of North Korea’s nuclear weapons as co-extensive.

The cover of a special “missile issue” of the North Korean paper, Rodong Sinmuniv

It is worth noting that even in a democratic society, where that identification is not explicit, its existence puts a very heavy burden on the social contract, perhaps even more so in a democracy, e.g. when it becomes personalized in the hands of the commander-in-chief with their finger on the button, as Elaine Scarry’s recent book, Thermonuclear Monarchy suggests.v

THE POLARIS AND ITS COUSINS

As I have suggested here, the Polaris and its related sub-launched family around the world are a type of weapons system envisioned at the height of the Cold War. The fact that similar systems are being developed in a new generation of nuclear-armed nations is depressing. But in fact, the mid-century vision of a large ballistic missile is being rethought. Several countries, including the US, Russia and China are developing nuclear-tipped cruise missiles designed to be launched by bomber aircraft. The US program calls for a thousand missiles under the label “Long Range Standoff Weapon” or LRSO. It is extremely difficult to shoot down an ICBM, which follows a mathematically predictable trajectory, although there are systems such as Iron Dome, Patriot that claim some success. Cruise missiles follow a guided path that is not trajectory-based, making them hard or even impossible to track. They can be highly accurate, and are armed with small nuclear warheads. This also means that these weapons can potentially be used “tactically” in pursuit of battlefield goals, bringing down the bar considerably for deployment. Their accuracy, by the way, does not equal reliability. Last year 4 out of 26 Russian cruise missiles launched from the Caspian Sea to hit targets in Syria some nine hundred miles away crashed in Iran. These were armed with “conventional warheads,” but they suggest why arming them with nuclear capability is alarming. Ironically, the LRSO is sold as a way to keep the US nuclear bomber fleet viable. Even former Secretary of Defense William Perry called them, “uniquely destabilizing.”vi

Nike nuclear missile launch controls, AKA “The Button.”

Nike nuclear missile launch controls, AKA “The Button.”

How does the missile occupy national space? We live in a world where promises of peace seem to be disappearing. We can as citizens, identify with the destructive power of a weapon, thought of as a deterrent. “My country is a powerful one. If my nation is threatened, we can obliterate the enemy.” This type of military capability is notable in that it doesn’t solve real problems we see in the world today, problems, such as terrorism, global warming and migration that may seem more pressing than the possibility of a nuclear war.

Nuclear weapons ask us to identify with power, power focused through very few hands, the ones on “The Button.” This focussing of power distorts democracy and creates an endless problem. That which is supposed to supply the security of the security state does the opposite. It’s real promise, and its appeal to desire, is that of a wiping out, of total obliteration, e.g. of “The Other.” It is notable that we are living at a time when people around the planet are rejecting being managed, whether with the Occupy movements or the Arab Spring, they are looking alternatives to representative systems of government that can only offer more or less mystified identifications with power, rather than real control over our lives. One can only hope that in the emergence of new forms of citizen power we will find both a more genuine democracy, and a final abandonment of nuclear arms.

Martin Lucas

Footnotes:

iActually it isn’t. Runny is probably derived from an Old English word for “meeting”.

ii“Object as Image: The Italian Scooter Cycle” Hiding in the Light (London, Routledge, 1988.)

iiiBonds of Love: Psychoanalysis, Feminism, and the Problem of Domination (New York, Pantheon, 1988.)

vThermonuclear Monarchy: Choosing Between Democracy and Doom (New York, Norton, 2014)

vihttps://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/mr-president-kill-the-new-cruise-missile/2015/10/15/e3e2807c-6ecd-11e5-9bfe-e59f5e244f92_story.html

| More: Uncategorized

War Means Not Having to Say You’re Sorry

May 26, 2016

Vietnamese crowds cheer Obama (May 24th, White House Photo, Pete Souza)

As President Obama tours the Far East, he is attempting to recast history in light of new geopolitical realities on a number of fronts. In Vietnam he announced that the US will end an arms embargo that is a vestige of the Vietnam War. Ben Rhodes, the Deputy National Security Advisor who has been the point man in developing the talking points around several recent Obama visits, including Cuba, was quoted in the NY Times:

“It does show how history can work in unpredictable ways,” said Benjamin J. Rhodes, a deputy national security adviser who spent time over the past two years luring Myanmar out of its shell. “Even the worst conflicts can be relatively quickly left behind.”

“As Obama Heads to Vietnam, Current Events Overshadow History” NYT May 21, 2016

Yet history doesn’t just disappear. For new generations, the relationship to past events is always tenuous and needs to be re-thought. One agenda developed in the Press around Obama’s Hiroshima trip has to do with the idea of an apology. Since 2008, every international trip made by Obama has been branded an “apology tour” by the right; he is sensitive on the issue. All of the White House pronouncements include the notion that there will be “no apology” for the atomic bombings.

Obama is certainly as sophisticated as any American President in his understanding of the role of historical memory in national and international affairs, and his interest in addressing global historical understanding. A recent Politico article asks “why this President sees himself as a force for confronting complicated truths about the past.” The answer, suggests author Dovere, is that he needs to force the world to deal with the past in order to deal with the future, suggesting that “…he’s going to Hiroshima to deal with North Korea.”

http://www.politico.com/story/2016/05/obama-asia-trip-hiroshima-apology-223446#ixzz49VNrY1iu

Obama certainly has a complex agenda in his trip. One goal, stated in 2009, is that of eliminating nuclear weapons globally. Another is that of addressing the new geopolitical realities of the region, which include a China that is more interested in pressing territorial claims, particularly in the South China Sea, and on the other, North Korea’s interest in developing its ability to deliver nuclear weapons.

So why go? The classic split for Americans of an older generation was the belief on the one hand that the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were necessary to save American lives in the event of a land invasion. Opposed to that has been the understanding that the bombings were the obliteration of entire cities and their citizens using a terrible weapon, one that works in a way that has left a legacy of ruined lives in the seventy years since.

It is worth noting that we are at a moment, now 70 years after these events, when those who lived through World War 2, are fast disappearing. As many writers have noted, it is exactly veterans and survivors, those who understand the cost of war, who help keep nations out of new ones. In fact, one question about Obama’s trip is whether an meeting with survivors is on his agenda. Certainly, the timing for a visit seems appropriate.

In a recent online post, Rhodes both pays tribute to Americans who fought in WW2, and underlines Obama’s anti-nuclear agenda:

“The President’s time in Hiroshima also will reaffirm America’s longstanding commitment — and the President’s personal commitment — to pursue the peace and security of a world without nuclear weapons.

Rhodes goes on to note that the visit will also underline the strength of the US relationship with Japan. It is worth remember that, on this journey, Obama will not go alone, but will be accompanied by Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. Abe as a politician is well to the right of Obama. He has tried hard to undo the pacifist legacy that is written into Japan’s constitution. As Global Voices blogger Nevin Thompson put it recently:

After spending most of the past 20 years living in Japan, to me 2015 seemed like a turning point for the country. 70 years after the end of World War II, and despite massive demonstrations all over the country, in September 2015, Japan’s ruling coalition, led by Shinzo Abe and the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), used cloture to force the implementation of new security laws that will allow Japan to engage in military action outside of the country. Thanks to this new legislation, Japan effectively renounced 70 years of pacifism and can now go to war again.

Https://globalvoices.org/2016/05/15/taking-back-japan-one-history-textbook-at-a-time/

One scenario suggests that Abe, who is looking at elections for the Upper House in July that are critical to being able to push through some of the changes he needs, sees the Hiroshima visit as a way to polish his credentials as a “peace candidate,” while at the same time reinforcing some of the more muscular aspects of the historical relationship between the US and Japan and creating more space to move Japan away from its pacifist legacy.

These goals on the part of Abe are not in conflict with either the goal of highlighting a move toward getting rid of nuclear weapons, nor the one of getting more participation from East Asian nations in balancing out rising Chinese power.

Hence for both leaders, the irony is that the classic branding of Hiroshima as symbolizing peace is something that they will use, wrapping themselves in the paper crane, as it were, while at the same time trying to renegotiate what the “Peace” that the symbol signifies will mean for a new generation.

While the President’s goals of focusing on the future, especially a nuclear-free one, are admirable, there are risks to this recasting the meaning of historical events. For Americans it is clear that we still need to “see” Hiroshima and Nagasaki. While nuclear weapons are viewed with appropriate dread, it is impossible to understand our ability to use, and promote the use of, aerial bombardment as a means of war, whether declared or undeclared, without contemplating Hiroshima and the post-War development of US military power. For the last seventy years, the trauma surrounding the role of the bombings in “ending the war and saving lives” has meant discussions of aerial warfare tend to be morally opaque. Even during Obama’s current Asia trip, the President took time out to announce the killing of a Taliban leader (and the people with him in his car) in Pakistan by a US drone. This was billed as a message to Pakistan, a country we are not at war with. It isn’t that the killing is not justifiable as an act of war against a leader of the Taliban. But, to have killing take place remotely from the air simply doesn’t seem as consequential as other forms of killing that involve actually putting troops in another country, for instance. But it means war is both potentially everywhere, and also, since it is undeclared, endless. Bombing of targets where civilians die is regrettable, but not necessarily space for serious national reflection on the wars we are in, and the cost we and more particularly others, pay. It should rate a serious re-examination of the meaning of war in the contemporary world.

| More: Uncategorized

Hiroshima Bound Screens at UnionDocs

March 12, 2016

I am happy to announce that Hiroshima Bound will have its first screening in the New York area at Union Docs in Williamsburg. The date is March 24th. The time is 7:30PM. The screening will be followed by a discussion with Reiko Tahara and Jason Fox.

For more, see: http://www.uniondocs.org/hiroshima-bound/

| More: Uncategorized

HIROSHIMA TRAILER UP

March 08, 2016

I am happy to announce that the trailer for Hiroshima Bound is now online. Editing by the admirable Steve MacFarlane.